1990 - 2022

Exactly. That’s what the whole middle classes are like back home. They go off and memorise Shakespeare’s date of birth and few rhyming couplets so they can sprinkle it in conversation around the barbie. “D’you think Kylie’ll bring the coleslaw? Ah, to bring or not bring, that is the question. Shakespeare you know. Born in 1564, strangely enough” “Yes. Died in 1616. Poor thing. Such a tragedy. Terrific bean salad Val.”

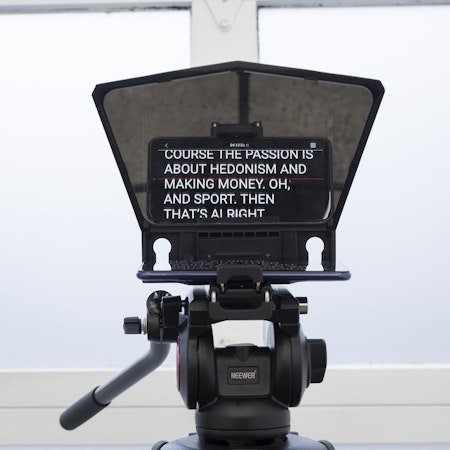

I am invited over to dinner to discuss Sam George and Lisa Radford’s Veronica Franco v Instagram. Sam is cooking. I had been very enthusiastic about The Dugong Sublime, the first iteration of this project, staged in This is a Poem at Buxton Contemporary in 2021. I was also enthusiastic about Sam’s cooking. Whilst as a studio neighbour, I had been privy to conversation in the project’s development and was concerned that my writing would only add another tangent to this expanded work: the dugong, the sublime, the romantic conceptualism of Mutlu Çerkez’s self-portrait and the forensic accounting of Stuart Ringholt’s personal belongings; propped up as these artworks were by nipples cast in bronze. The Dugong Sublime addressed This is a Poem’s curatorial premise by bridging the fields of art and poetry in its very structure and mode, working between the fields as the term ekphrasis suggests. The artwork was not an annotation, an illustration or a typographic NOISE, it was a series of nodes or perhaps more fittingly buoys, to swim between. Another buoy in the work was the accompanying performance, a type of language collage, a syntactical disruption or play with Hannie Rayson’s 1991 script for Hotel Sorrento. Staged on a mezzanine walkway, a type of architectural jetty to the main installation, the audience were forced to sit underneath the mezzanine, perhaps alienated by the cultural references, or lamenting the diminished role of art and poetry in Australian life. I couldn’t help but identify with the snob in The Dugong Sublime. Both cringing and delighting at the disruptive space of Tina Arena’s pop song Sorrento Moon in Hotel Sorrento – the canonical Australian play (and film), which at the time, I had never seen or read. Between the dinner party banter on cultural cringe, I take another slice of focaccia which Sam has generously baked.

I don’t write autobiography. I write fiction.

My dad was always excited when he bought lagana home from the Greek bakery. While I am one of those people that lines up for bread now, in 1993 bread was bread. I probably had my first focaccia, lagana’s Italian equivalent, with my new friend Nicole who I had met with another group of friends from my high school’s sister school. Living the aspirational dream — that was, to actually have friends in amongst the new social milieu that I found myself in. The schools were half filled with the children of immigrants, but there was also an intoxicating mix of Anglican revelry and alienating contestation of social and cultural capital that was heady and fraught. Nicole was great. Her parents would write permission slips so that she could attend weekday protests outside Mitsubishi headquarters and would donate to anti-duck hunting groups in lieu of her attending protests out on the field. We were at the Billy Guyatts food court on Bourke Street when she encouraged me to order, like her, a toasted focaccia with cheese, avocado and sun-dried tomatoes.

But the fact is, in this country there is a suffocatingly oppressive sense that what you do as an artist, is essentially self-indulgent.

1997 marks my first crush at art school, which was not romantic but rather, artistic. Oliver and I shared a studio space and I thought he was the coolest. Emerging out of adolescence, Oliver made the kind of artwork I wished I could make—clever, expressive and with the attitude of a bass-player in a rock band. Two particular works still resonate with me, and they’re all about the mother—his mother. In the first, Oliver would collect and trace his mother’s un-self-conscious notepad doodles. The collection of doodles would be scribbles one used to find next to your home phone landline in the margins of an address book. From pen marks, no bigger than a thumb-nail, Oliver would meticulously translate these doodles into six-foot paintings. This terrifying enlargement would reveal the inconsistent viscosity of the inked line, a sort of clinical reframing and a distancing of the cute flourishes of the original doodle. In the second work, Oliver’s audience would be subsumed by a text-based wall-work—a singular BOOB sprawled across the corridor wall leading to our studios. The usable walls of the art school were probably no taller than the standard 2400 mm sheet of plywood, but I am now imagining expanses of black paint covering the entire height of the art deco building that was once a “working men’s college”. While I had a crush on Oliver, he was, in many ways, crushing on a generation of American artists searching for the sublime. His work echoed the ironic appropriation strategies that were framed as critical exemplars—or were at the very least, the orthodoxy of our art school education.

You know what I think? I think that melancholy is something that men don’t understand. Australian men, dare I say it.

Mitchell died a fortnight ago. I didn’t know Mitchell. He was the partner of a colleague of mine. I went to his memorial service at the St Kilda RSL to show some support. A quick glance of the memorial’s program revealed that this might not be the sombre gathering of grief I initially thought. Steve Vizard was listed as MC and there seemed to be a line-up of bands playing. Looking around at the packed RSL, was a community of ageing punters, integral to St Kilda’s role in progressive culture and art, prior to the last 30 years of gentrification. The memorial transpired to be a very local event, revealing a particular picture of the Australian comedy scene. Always suited, Steve Vizard was of course the host of a late-night talk show before the internet would allow for a broader awareness of how derivative his format was, of David Letterman’s. My teen encounter with Vizard was when he was at the peak of his commercial and mainstream success. Behind his success was a team of writers, including the late Mitchell Faircloth, who had tested their comedy on community radio for years prior to the 1990s. During this time, comedy traversed class distinctions—from the Melbourne University Law Review to the back blocks of the outer suburbs. I guess the common thread of this laugh-filled memorial was the melancholic blokey-ness that tested our current moment of social propriety. Following three hours of laughter—and different types of laughter—my dear colleague Marian, with the most dignified composure, pushed aside Mitchell’s lynchpin role in the comedy scene and reflected on their shared suburban life and the last time they went to the local shops together in Bentleigh to buy some produce for a Jamaican gumbo.

What’s wrong with it is, if you’re preoccupied with a need to be certain, you do not allow yourself to see the contradictions in things. And when you don’t see contradictions, your perceptions are totally blunted. I’m not the least bit interested in being certain about anything.

As I grabbed my fourth piece of focaccia topped with charred chicory, Lisa and Sam mapped out the set of relations that would play out in Veronica Franco v Instagram. As I relished the food that evening, I also relished the confounding absurdity of this new work—the poetry of the 16th century Italian poet and courtesan Veronica Franco; her representation in Renaissance painting; the politics of freeing the nipple on Instagram; the middle-suburban brothel in the 1983 film Risky Business; and a 1991 Maria Kozic painting of a boob. Amongst all this, Lisa made a remark on the political dimensions of the local that provided me with the keyword search for my belated viewing of Sorrento Moon, I mean Hotel Sorrento.

You’ve got a spare ticket to the Big Day Out, 1993. Which mate are you going to call?

Adam Zwar @adamzwar – Nov 16, 2018

Over the last couple of years our sense of the local has intensified of course, instrumentalised as a set of xenophobic boundaries and an opportunity for the state to control bodies. Some of us have also had the fortunate opportunity to reimagine the local—slowed down—as space of comfort and care, the flip side of this fraught condition, as we bounce back to busily trying to find cheap flights to Venice and overcommit ourselves to work. In Australia in 1993, this discussion would be framed through the parochial. In that year, some of the results of the 2022 Australian federal election would be inconceivable. In once safe seats, multiple and at times conflicting understandings of the local were enacted as a critical imperative across the political spectrum to counter the dominant paradigms of the respective major parties. 1993 was also the year that provided the backdrop for one of the funnier memes and the year our current Prime Minister went to the Big Day Out to see You Am I.

Two figures sit on the end of the jetty. It is dusk. The man is fishing. There are remnants of fish and chips in white paper lying between them. She is reading Melancholy. He is staring out to sea.

Spiros Panigirakis

Interim Head of Fine Art, Art Design and Architecture, Monash University

*Italicised excerpts from Hannie Rayson, Hotel Sorrento, Sydney: CurrencyPress in association with Playbox Theatre Company, Melbourne, 1990

**Adam Zwar tweeting his Tweet: https://twitter.com/adamzwar/status/1527394400069877763