How do we perceive when the parameters relied upon to frame what we hope to discern are not fixed, rather fluxed? When the edges steadily become less and less focused, penetrating and clouding our known knowledge? When what is present is the manifestation of gnostic knowledge, concerning those with a specific esoteric understanding, the carpenters sculpting these fluxed parameters? The collaborative work of Lewis Fidock and Joshua Petherick is representative of this clouded state; they are these carpenters.

From their earliest works, Fidock and Petherick have engaged with artifice to disrupt our perception. Rather than embracing the preference for simplicity laid out by Franciscan friar William of Ockham in his problem-solving principle Occam’s razor — a concept Fidock and Petherick referenced in their first collaborative exhibition, A Cut from Occam’s Razor (Punk Café, Melbourne, 2016) — they opt for hypotheses presenting numerous assumptions. Their aim is to leave both their works and larger exhibitions somewhat occulted: cut off from view by a gathering of imposing specific somethings. They achieve this through the traditional artistic foundations of materials and techniques, carefully considering what should be used and how it should be applied to achieve their conceptual goal; methods they accompany with a detailed attention to atmosphere — something often underappreciated or unnoticed. The recognisability of their techniques and deliberations highlight that Fidock and Petherick’s practice is not intended to be totally darkened. Numerous elements within their work draw on familiar forms and references, whilst frequently engaging the viewer at an emotional level. This results in art that speaks to the real world and its contained ontology, but coming from a parallel space, perhaps best described as pertaining to the history of lost futures.

The fluxed parameters of Fidock and Petherick’s artistic undertakings, whether objects, sculptures, video works, installation practices or articulations in atmosphere, play with ideas of time and place and the narratives they adhere to. Hence the view that perhaps their creations are not holistically present, but rather unstable in their temporal whereabouts. When engaging with these collaborative works it often feels as though their origins are linked to an archaeological dig searching for Templar treasure lost on a Grail quest (say Wreath from 2016, a crumpled skin-like relief seemingly taken from a section of a Medieval church). In other instances — perhaps evoking speculative futures — one is reminded of cyberpunk cultures where capital has accelerated to the point of near annihilation (their Sleeve works from 2017 are perhaps most fitting here, disfigured artificially-patinated pipes that could hail from an unliveable city of 2049). In both instances, it feels as though these objects could very well be contained within our historical timeline, but equally so, could sit outside of it in a parallel timeline. In numerous other examples, we perceive both past and future — of this timeline, or not — whilst remaining conscious of a presentness. This cross-pollination is perhaps best described in aspects of Mark Fisher’s reinterpretation of Jacques Derrida’s Hauntology (a portmanteau of haunting and ontology), in combination with Fisher’s conceptualisation of lost futures. By selectively picking at Fisher’s theories, one can start to make sense of Fidock and Petherick’s fluxed state. Here we can appreciate how their works materialise memory or history — the artefacts found in an archaeological dig; as contrasted with a concern for speculative lost futures — the unliveable city of 2049. It is through this amalgam of being haunted by both the past and lost futures where one finds a grounding for much of Fidock and Petherick’s work. Or as Fisher summarises:

Everything that exists is possible only on the basis of a whole series of absences, which precede and surround it, allowing it to possess such consistency and intelligibility that it does.*

Even with this dislocation of time and place, the present still remains vividly discernible in their practice. In the first instance, Fidock and Petherick’s acute attention to space — with respect to the exhibition context — phenomenologically entwines the viewer, making their presence eagerly felt in the moment. As the French dramatist, essayist and theatre director Antonin Artaud noted in his manifesto, Theatre of Cruelty (1932):

In a word, we believe there are living powers in what is called poetry, and that the picture of a crime presented in the right stage conditions is something infinitely more dangerous to the mind than if the same crime were committed in life.†

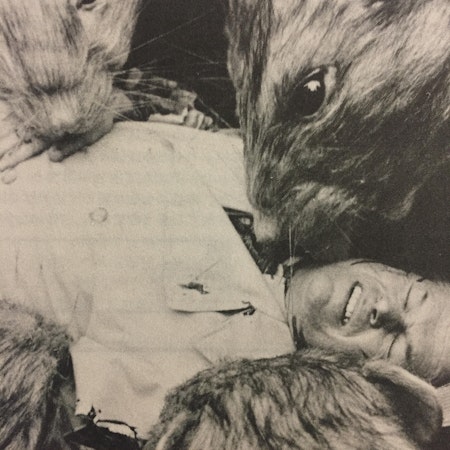

For Artaud, this new type of theatre called for a communion, or magical exorcism, that had the potential to liberate the human subconscious and present man back to himself. This was to be achieved through sensory means (what Artaud perceived as a type of cruelty): by connecting with emotions of shock and confrontation, fused within sound, scenery, gesture and lighting. It was about disrupting the relationship between audience and performer, a sentiment which echoes in Fidock and Petherick’s practice.‡ When you are in their space, within the company of their objects, certain emotions and sensations are evoked: isolation, uncertainty, melancholia, nostalgia, paranoia and unheimlich are greatly felt. Their exhibition Weevils in the Flour (Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne, 2020) presents a heightened atmosphere through modifications to the very structure of the white cube — an act Artaud would fondly approve of. Doing away with the traditional lighting, Fidock and Petherick rely instead on the flickers provided by a sea of lanterns (Weevils, 2020) and the glow of a screen, whose imagery presents a modern-day Templar’s steed as it jousts its way across barren roads, snaking through forgotten goldfields looking for a righteous quest to a soundtrack of spectral drones. The ceiling has sections removed, breaking the third wall of the exhibition, all while their performer (Character, 2017) moves with an OCD-like compulsion, its umbilical cord still attached, thus only being afforded so much opportunity on stage. It is through such additions and adaptations that the artists enhance the relationships between space, objects and audience, leaving said audience immersed in atmosphere — and the present.

Fidock and Petherick’s presentness is further explored as the viewer is — in most cases — able to find a recognisable entry point into the work, whether through form, concept or emotion. From the more discernible: such as their grouping of light works, the aforementioned Weevils, reminiscent of lanterns lining the walls of underground tunnels and chambers of some Arthurian legend. Or less literally, in work like Collector (2019): a large corduroy-covered fiberglass abstract sculpture that evokes elements of Soviet structures, crude oil storage tanks, small research submarines or atomic bombs. A work which equally conjures up feelings of nostalgia by means of its materiality; recalling furniture and clothing from the late 1960s, a time beset with corduroy, which the late 20th and now 21st centuries continue to replicate — involuntarily acknowledging a lack of new avant-garde achievement. An example Fisher would define as the result of “the slow cancelation of the future”:

In 1981, the 1960s seemed much further away than they do today. Since then, cultural time has folded back on itself, and the impression of linear development has given way to a strange simultaneity.§

This collision of presentness, fused with the past (alongside nostalgia/memory), speculative futures and parallel timelines, or as Fisher notes a strange simultaneity, engage with both the recognisable and the distorted. This is the grounding that Fidock and Petherick offer.

—

By Jack Willet

* Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Alresford: Zero Books, 2014, 17-18

† Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and its Double, Surrey: Alma Classics, 2010, 61

‡ Natasha Tripney, Antonin Artaud and the Theatre of Cruelty, London: British Library, 2017, https://www.bl.uk/20thcentury-

literature/articles/antonin-artaud-and-the-theatre-of-cruelty

§ Mark