The exhibition feels like a very still spring night spent outside in a friend’s backyard. There is a lingering warm glow from the daytime that has now with the arrival of night, cooled right down. It does seem as though there should be a light breeze but instead an almost claustrophobic stillness has formed around me. It’s not too hot but I do start to feel the sweat linger and slowly build up on my body; sticky to the touch and with nowhere to go with the omnipresent stale air. When the wind has stopped blowing in this way, and everything begins to stand still, it allows me a chance to see things around me differently; a space that should be familiar, has now turned unfamiliar. This transformative stillness I’m feeling demonstrates the uncanny ability for a safe and familiar space to shift to something unknown—the objects around the yard, the buildings in the background, the trees nearby—are all seen in a different way, and with this, shift in context. The gentle laps of the pool have become a monolithic form; like a large shard of glass. The liminality that the stillness presents makes it more challenging to distinguish friend from foe. This sense of transformation also impacts my impression of time – I’m not sure if two minutes have gone by or twenty.

I feel a sense of agoraphobia walking into Rob McLeish’s exhibition HEADLESS, a slow burning sense of panic. Maybe it's the social anxiety and two years of on-and-off lockdowns in this city, or perhaps the way that McLeish’s show makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up; or a bit of both. I feel like I’m at a party and no one else has arrived yet. Or even more accurately still, someone is watching and observing mine, the viewer's relationships between the objects and the space. As I progress through the show, there are times, my memory reminds me, almost an unconscious psychological warning that these visual cues I am seeing, have been deliberately placed into this new liminal formation and context, to challenge my/our perceptions of objecthood.

McLeish arrived at art practice, somewhat late, following an initial career as a graphic designer. For years he worked as an untrained artist, with no formal pedagogical art training; however after five years of exhibiting in Sydney and Melbourne, he began a Masters of Fine Arts at Monash University. Today, McLeish’s carefully crafted practice produces psychologically engaging works with a distinctly discordant edge. Traversing sculpture, installation, collage and drawing, McLeish has incrementally constructed an idiosyncratic visual language that is brazenly ambiguous. McLeish's oeuvre thrives in the space between restraint and excess; power and perversion; the mundane and the miraculous. The 2021 River Capital Commission at Gertrude Contemporary brings together fifteen years of McLeish's sculptural practice. The constellation of works, titled HEADLESS, is the largest survey exhibition by the artist to date.

Consistently throughout his process-based practice, McLeish has maintained an interest in an artist’s perceived value within the realm of fetishised formalist perfection, capitalist outputs and creative originality. McLeish is interested in how this has played out within art history, but also how this applies to the artist’s own attitude towards art practice – where he uses humour and irreverence to poke fun at it as an often bourgeois, lofty pursuit (take for example the artist’s instagram handle @pissingintheinfinitypool). The fetishised object has been theorised widely and most often through a psychoanalytic lens. Some theorists claim that the more perversely risky a work, the greater an audience’s attraction to it. Others speak to the artist’s psychological pathos and the Freudian school of thought regarding childhood trauma.

How McLeish engages with the notion of the fetish is best defined by art historian and theorist Donald Kuspit when he says: “the fetish reflects the artist’s anxiety in creating that new object—the fear of impotence, inconsequence—at the same time that its production signals a triumph over that anxiety: potency and significance.” (fn) Indeed, in an interview conducted for McLeish’s 2021 Neon Parc exhibition Distortions, the artist says the above in his own words, describing: “this parody of the artist who’s overburdened with absurd weight of their own potential creative output; encumbered by their grandiose imperative to bring something ‘new’ into the world, lugging this ridiculous burden of ‘creativity’ around.” (fn) Through this awareness, we can understand that McLeish is critiquing not only his position as an artist, but also the wider systemic pressures placed upon producing art in ‘the contemporary’.

McLeish's sculptural works consistently reference and deconstruct the figure, the bust and the monument. In HEADLESS, we can see this played out in McLeish’s 2018 sculpture Sinkhole Holiday (Suspended model in black 001). Here we see a subversion of a classic bust and plinth configuration. The 'bust' appears to be precariously perched within a black plastic sheet that has been stretched across the top of a minimalist, rectangular steel frame. The unlikely configuration is haphazardly held together by gaffer tape. Instead of a work depicting a formalist translation of a studied figure, audiences are presented with an abstracted shape; a violently reduced figure conveyed in a strange, temporal and unfamiliar material. The black surface is reminiscent of abstracted fleshy insides, bodily waste, oily grime or muddied dirt. Indeed, the figure itself seems to be sinking under its own weight, slipping into its own filth, and in doing so dragging down the plinth; sagging below the very structure that should be there to support its presentation. Despite the appearance of temporality and degeneration, the black plastic sheet, the gaffer tape and the inchoate figure are all fabricated in epoxy resin – cast as a rigid monument. The result is perhaps a critique of ‘the contemporary’, or at least a subversion of dominant art historical tropes.

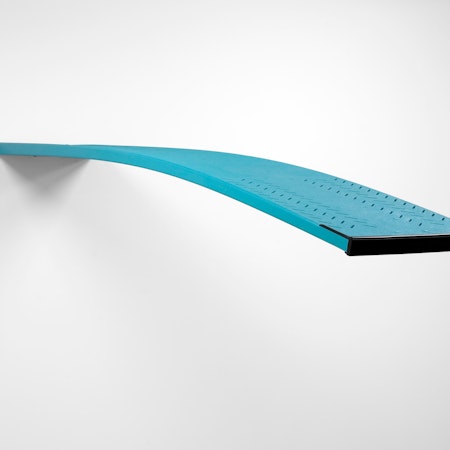

The relationship between the fetishised, status and formalism is also explored by McLeish beyond art history to a wider critique of popular culture. Similar to Armen Avanessian’s Miamification, we can see McLeish’s interest in the hyper-fake, particularly through the constructed environment of the swimming pool and everything that these environments of artifice come to represent. He explores how these water bodies manifest status, leisure, exhibitionism and desire. In HEADLESS, we see a continuous reference to swimming pools and other bodies of water: whether through Afterparty, a blue diving springboard frozen in motion; or stainless steel pool handrails and hot water bottles in the HEADLESS series; a toilet plunger in Le Concierge Acéphale; and in Automatic Faggot For The People (AKA Concept Fatigue), a stainless steel fusion of urinal/drinking fountain as minimalist sculpture.

Taking this idea further, McLeish’s methodology can be defined by two opposing actions. These can be understood as conditioned and unconditioned processes: the former are structured, fixed, premeditated, planned and formally ‘tight’; the latter are gestural, spontaneous, intuitive and 'loose'. This tension is highly important within McLeish’s practice as he oscillates between these two roles, traversing a sort of pseudo-psychological pathology in his practice and drawing on a ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ approach to art making. Returning to Sinkhole Holiday (Suspended model in black 001) we can see both the conditioned and unconditioned at play. The conditioned: the commercially fabricated, symmetrical, geometric steel plinth. The unconditioned: the ambiguous black form grafted together through a series of innate, quick gestures.

In HEADLESS, McLeish presents a rich deep dive into fetishised objects, the contemporary and the artifice. Placed in concert with his focus on latent tension—as provided by the conditioned and unconditioned aspect of his process—allows the artist to present a constellation of mostly uncomfortable stagings; pseudo-environments operating as possible psycho-scapes for the audience.

Footnote: