31 July -

29 August 2009

Studio 12

200 Gertrude Street, FitzroyCatalog text produced for Gertrude Contemporary and Art and Australia Emerging Writers Program -

Ardi Gunawan is unconcerned with results. His is the kind of work that privileges process over product. It seems almost incidental to his practice that any object be realised at all. And the persuasive immediacy of his experiments, narrowing the gap between art and life make me suspect that anything more concrete would be pretence anyway. A surfeit. The

objet d’art seems conservative, even quaintly outmoded, set against Gunawan’s brand of post object art; superfluous to the real work that occupies the artist. By contrast, here, the ‘work’ is precisely that and hardly more.

Dual video screens loop raw footage of what appears in one – by the white washed look of things – to be a gallery performance with two actors which could very easily pass for nothing much happening at all. One performer, the artist, tunes and detunes a guitar momentarily and with seeming aimlessness before setting it aside, ostensibly in favour of a set of house keys which he proceeds to untie. The other figure paces, referring intermittently to a sheet of paper in hand. My guess is that, far from being arbitrary, his casual glances at whatever is written there will direct his next move. My assumption is

confirmed: upon reading it, he stands still, hands at sides, for the next thirty seconds or so. The second screen echoes the action of the first, apparently a dry run of the main event. (1)

What sets this re-enactment of everyday activities apart as art? It doesn’t readily announce its status as such; rather, it is decidedly un-‘spectacular’ in the sense of the word so often used to describe contemporary modes of creation. And there’s no trace of the old ‘aura’ of the art object to be found either. But of course, by now we are comfortable in the knowledge that the era of the aura is behind us. The once alleged paradox of non-object art has been investigated and resolved by previous generations so that not only is Gunawan’s performance validated by a strong historical precedent, but it cannot be said to be all that radical an approach by today’s standards.

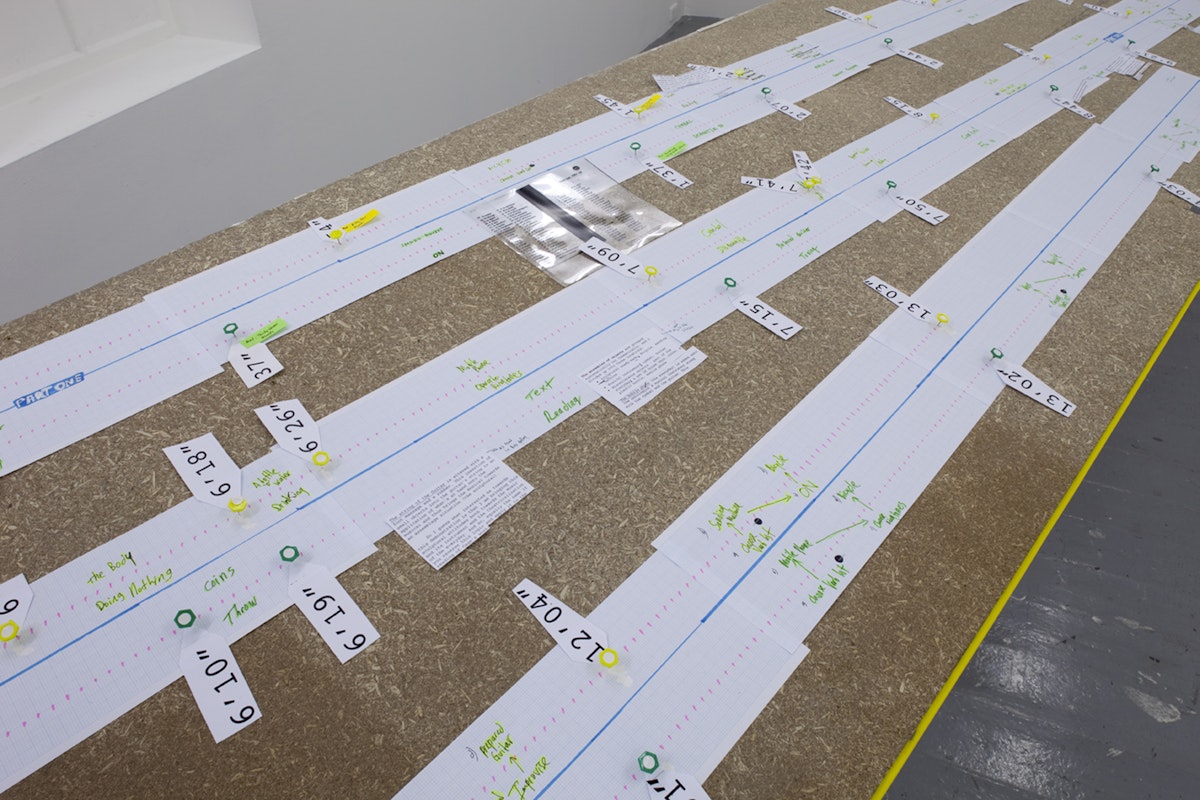

Gunawan here takes his cue from John Cage. He applies a Cagean methodology to compose an aleatoric score that reads as a set of instructions to be realised as the scripted performance appearing on screen. Using the I Ching (2) as his divining rod,

Gunawan isolates, from vast pools of variables, the kind of event or action to take place and its duration. Chance is a ready collaborator in his methodology. In the fifties and sixties, these kinds of approaches broke radically with rigid definitions of art and music. This time around, Process Art takes on a particular resonance that speaks of something more and of specific relevance to our age.

In one of his more compelling claims for the conditions of contemporary art, Nicholas Bourriaud spoke recently of the artist as traveller, negotiating the rocky terrain of our current moment through the ‘journey-form’; work which traces an historical or geographical trajectory.(3) It is to speak, in part, of a contemporary impulse toward the translation of ideas and information across disciplines and formats, through space as well as time. This is symptomatic of a sense of history that is becoming increasingly fluid. Malleable. Free to skip and fold back into itself; to map and abandon new territories along non-sequential and multi-directional lines of thought. It is a sign of a new willingness to consider multiple perspectives, that allows networked or rhizomatic pathways to be forged in the space vacated by an old linear or arborescent conception of history.

And this is, I think, the mood that Gunawan’s experimentation channels. His work is open ended, revisable, temporary and latent with potential. Each new instalment of his work in a gallery context is more appropriately an occasion, not for Gunawan to stage recent finished work, but rather to publicly enact aspects of an ongoing and evolving wider project that is in a permanent state of flux. In perpetual draft form, his work is an endless deferral of having to come up against the finished, ‘closed’ work of art. Performances are enacted, re-run and replayed, written and rescripted to cycle through infinite, random permutations. (4)

A sea of circulating elements, objects and ideas, his own or sampled from the past, alternately crystallise and disperse, organised by the non-linear laws of chance. Today, more than ever, it seems that the universe echoes this schema, dictated by chance and little more. In a Kafkaesque inversion, Gunawan points to this experience of the existentialist subject by scripting, staging and overstating the banal to the point at which it deteriorates into absurdity.

Yet this is not as bleak as it might sound. Gunawan explains his wider project as a protracted meditation on forces such as chance and entropy as material considerations. He seeks to give form not to perceivable elements encountered in the real world, but to invisible ordering forces abstract in nature and recognisable only intuitively. Gunawan, like Cage, who explained the use of chance as “…the belief that all answers answer all questions”(5) appears to be uncovering a universally applicable logic from within an otherwise seemingly chaotic world. What is chance? Could it really be evidence of some natural order beyond our conception or is it just the random manifestation of chaos unfettered by purpose or cause? Something tells me that if it came down to the toss of a coin, with order as heads and chaos as tails, Gunawan would throw heads every time.

---

1. This ‘main event’ was indeed a gallery performance, entitled Time-Racing and performed with Michael Farrell at Bus gallery,

Melbourne earlier this year.

2. An ancient Taoist anthology of oracles based on picture symbols or hexagrams and indexed according to the permutations of coin tosses.

3. See texts and symposia in conjunction with Bourriaud’s 2009 curatorial project Altermodern, the fourth Tate Triennial.

4. Similarly, Gunawan’s recent sculptures are assembled from found objects, then dismantled and their elements re-used in later works.

5. John Cage in the introduction to I-VI a collection of lectures from the Charles Eliot Norton series delivered at Harvard

Unversity in 1988-89.

BROOKE BABINGTON