27 October -

18 November 2006

Studio 12

200 Gertrude Street, FitzroyCatalogue Text produced by Melissa Amore for the Emerging Writers Program

‘I had a dream a small anodized metal flying machine landed on my eye. As I reached to touch it, a cool fluid ran out of my eye and down my face. Sometime after this dream, a drawing pin punctured my eye. To check if I could still see colours correctly a doctor poured different fluids into my eye. Fearful of losing my vision, I thought how can something so traumatic - be so beautiful.’ - Michelle Ussher

Extra-Ordinary Inquisition

Michelle Ussher’s unruly compositions could well be the outpourings of a manic, hyper-imaginative child. Riddled with sci-fi imagery, mythology and folklore tales, her complex mindscapes capture the inherent contradictions of human interaction and destruction.

Ussher’s fictitious characters are immersed in an imaginative disfiguring of form. A cornucopia of overgrown mushrooms, demons, trees, blossoms, insects and a fanciful palette infers a perplexing eroticism and trickery with the natural. The work ventures beyond the apparent depiction of land and place, of colloquial Australian campsites. Ussher’s landscapes have become mindscapes –revealing a sublime and dream-like psychological space.

Born in Moree, raised in Kempsey and currently residing in Melbourne, Ussher’s work is concerned with adaptation, both in technique and in content. Her work interbreeds the rural and the imagined suburban, cultivating the curious overlap between the untreated and tampered landscape. This transition creates a powerful dialogue that hints at a harmonious meeting of the natural and constructed culture.

Her exploration develops from borrowing images of objects and re-assembling. Avoiding site-specific reference to time and place, Ussher sketches new pictorial worlds where boundaries unite. ‘Maybe it’s like the idea of being Australian’, Ussher comments. ‘We are still trying to define ourselves by other things and in a sense my work does that. I draw from other things to question identity and relationships.’

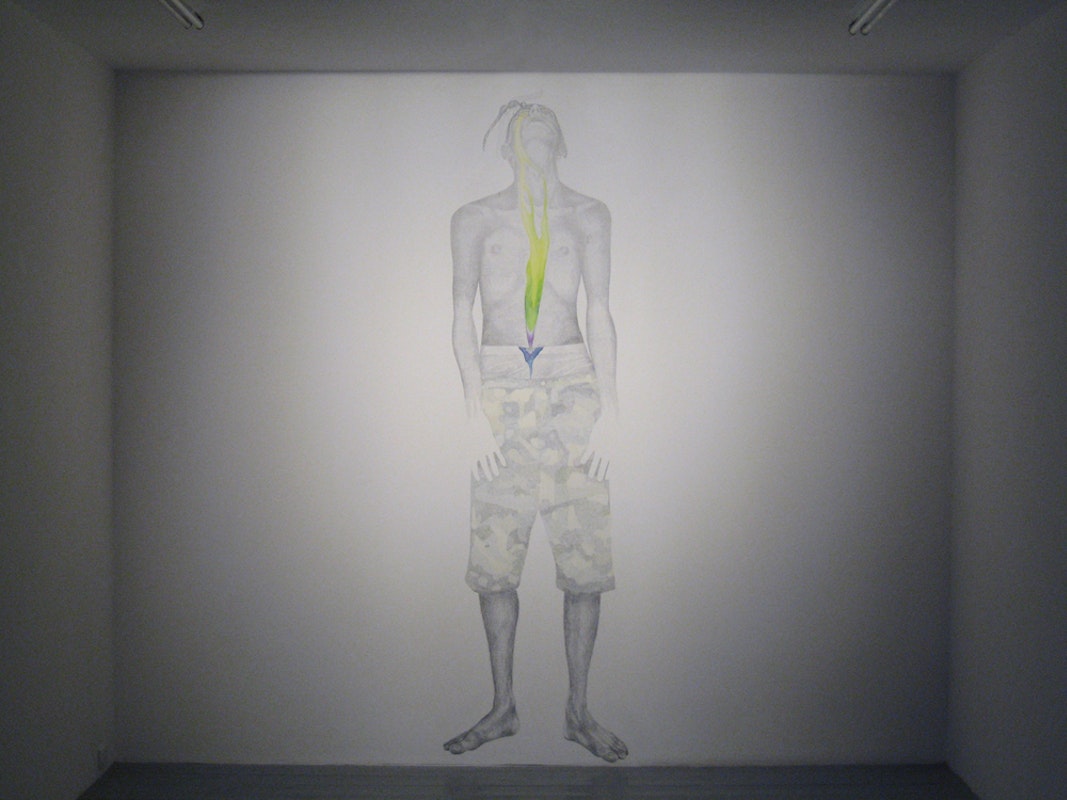

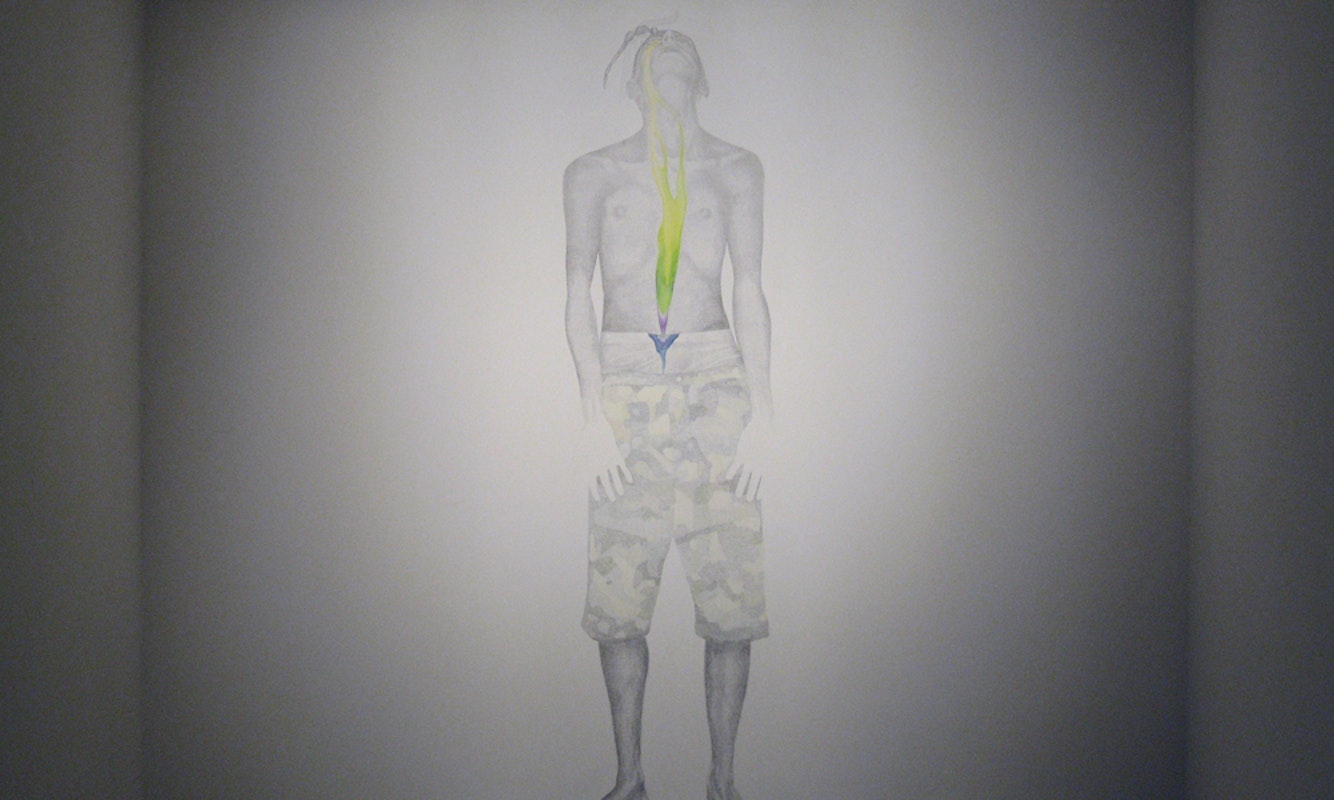

Void of landscape and random objects, the wall drawing Dragonflyeye portrays an esoteric dialogue between a demonic dragonfly and a pubescent boy. The body appears vulnerable, immobilized, yet charmed by this Epiprocta. The dragonfly could be healing or infecting, seducing or secreting, yet the boy stands open, ostensibly relishing the insect’s advances. Free of struggle, both boy and insect become symbiotic.

The dragonfly essentially transcends the boy’s left eye and a disparate union of the anatomy could be at stake. In both Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis and the more contemporary remake of The Fly by American director David Cronenberg, vision is paramount as a central notion of self-awareness. The boy could be experiencing a multifaceted process of ‘seeing’, as the loss of his left eye is reinstated by the dragonfly’s heightened consciousness. The insect becomes entangled with the host body exuding a viscous, slippery fluid.

The outpouring of fluorescent verdant substance streaming towards the subject’s genitalia hints at both an infectious pleasure and a metaphysical reaction to the foreign exchange. ‘This may be suggestive of the idea of a beautiful violence,’ Ussher comments. These pulsating greens and yellows recall the multiple hues of science fiction, yet Ussher’s colours are extracted from nature itself: ‘The colours originated from a eucalyptus leaf,’ says Ussher. ‘It’s hard to believe these colours derive from something natural – it appeared so supernatural.’

Ussher’s stringent, yet recreational approach tests humanity’s relationship with the natural environment – examining how we interact, control and form abstractions from it. The work itself being a larger-than-life wall drawing, challenges the spectator’s spatial orientation. Dragonflyeye breeds in the viewer’s space.

The notion of an extra-ordinary synthesis between boy and insect is challenging, yet as humanity is indubitably co-dependent with nature, it is only the fear of the unknown that creates a seemingly obvious partition, as the barrier of language amongst all species is the fundamental underbelly to prejudice. If it were possible for adult humanity to purge its inherent prejudices, to obliterate all preconceived associations to objects, places and things, the result would be one of child-like wonder.

Ussher experiments with this notion, challenging her audience to re-learn associations to the external world. The ‘oddities’ discovered in the mindscapes provoke a powerful sense of mystery, revealing the vulnerability of humanity and the natural environment alike.

This unique re-telling of foreign seduction and interconnectedness between a boy and a dragonfly acknowledges the extra-ordinary inquisition in life itself – as we all undergo the perilous crossing of adaptation. Dragonflyeye tickles at both the grotesque and the flirtatious, highlighting the intrinsic gravitational current bleeding in the phenomenon of the natural.

MELISSA AMORE